Each school year presents its own particular challenge. We survived learning to read with only a few battle scars. Then we clawed our way from one-sentence, grudging narrations to fluent paragraphs. But this year, with a fourth and fifth grader on my hands, I find myself circling back to the beginning.

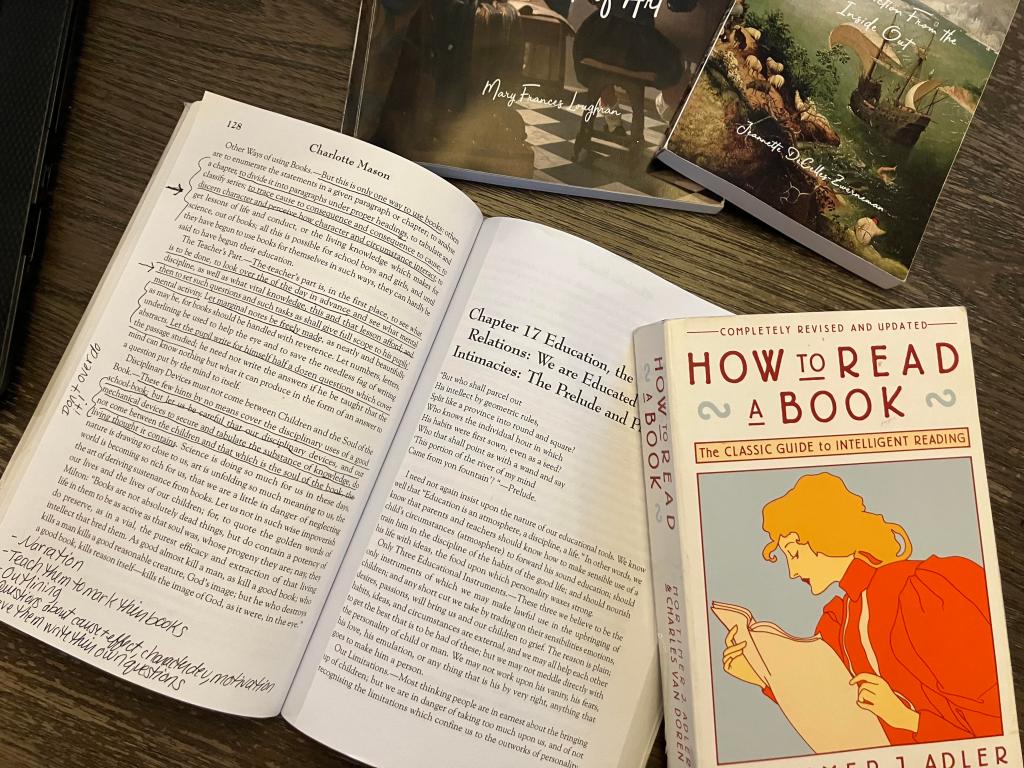

I want to teach my girls to read. No, I’m not talking about sounding out blends and decoding words. I mean what Charlotte Mason calls “intelligent reading” or “how to use school books” (School Education 127).

Narration is always Charlotte’s primary assignment for school readings. She calls it “the simplest way of dealing with a paragraph or chapter” (127). I love her unapologetic practicality. Despite all of narration’s glorious benefits, we harried mothers should feel no shame in appreciating the simplicity of just telling back. No need to strain our brains with worksheets, cute crafts, or entertaining activities. Read, narrate, absorb, retain.

Yet some days our routine feels more like read, narrate, close the book, and go on to the next thing. That’s why my attention snagged on a phrase that seems to get little notice in Charlotte Mason circles. She says that “narration is only one way to use books,” and she goes into great detail about other ways:

… to enumerate the statements in a given paragraph or chapter; to analyse a chapter; to divide it into paragraphs and headings; to tabulate and classify series; to trace cause to consequence and consequence to cause; to discern character and perceive how character and circumstance interact; to get lessons of life and conduct” (128).

These practices are not only “possible for school boys and girls,” but so important that “until they have begun to use books for themselves in such ways, they can hardly be said to have begun their education” (128).

What is good reading? How can we really learn from books? These questions have dogged my steps from the beginning of our homeschooling journey. I know Charlotte’s decree that narration should happen after a single reading. But sometimes in my fear of deviating from Charlotte’s wisdom, I’ve taken the single reading mandate to mean we could only skim the surface. I think these other ways give us permission to dig deep.

Good reading equals good observation. Good observation is facilitated by good questions. But what are good questions? I’ve seen a lot of complicated, leading, and downright dumb questions in literature study guides, and I’ve come to realize that the best questions are embarrassingly obvious. The best questions simply help us to look closely, and as we’re looking, to really see.

Here is my list of good reading questions culled from the sources listed at the end of this post.

Number 1: What do you see? “What do you see?” works for nature study, picture study, poetry, and literature. Consider this question a matter of collecting the work’s details, especially its sensory details (DeCelles-Zwerneman). Don’t just ask “What do you see?” but “What do you hear, smell, touch, and taste?” The traditional journalism questions can help immensely too: who, what, where, when, why, how, how many?

Number 2: What is happening in the story / picture / poem? The next question begins to gather these scattered details together into a coherent understanding of the work’s “subject matter” (Loughran). We might also ask questions of “motivation”: “Why does a character do what she does?” (DeCelles-Zwerneman). Another fruitful question is “How do the characters grow or change?”

For a nonfiction work, ask “What is the book about as a whole?” and then, “What is being said in detail?” (Adler). These questions provide natural opportunities for narration.

Number 3: How does it move us? (Loughran) In other words, what experience does the work give us of the human condition and of transcendent reality beyond our human plight? This question is not meant to encourage self absorption but rather to teach us to feel what we ought to feel, to take us out of our small worlds into a larger reality. As C.S. Lewis said, reading provides “an enormous extension of being,” allowing us to see through eyes other than our own.

For a nonfiction work, we might instead ask Is it true? (Adler)

Number 4: What elements of the author’s craft give us this experience? (Loughran). In art, we look at color, composition, line, and brushwork. In poetry, we listen for rhyme, rhythm, and alliteration. In literature, the interweaving of character, plot, setting, and imagery draw us into the world of the story. In nonfiction, a persuasive argument carefully constructed gives us a new way of viewing the world.

Number 5: So what? For nonfiction works, ask “Why should I care?” We could also ask, “How does this change my thinking / my way of looking at the world?”

Number 6: “What do I wonder about?” (Laws). Charlotte believed students could learn only by finding answers for themselves to questions they asked themselves. She advised, “Let the pupil write for himself half a dozen questions which cover the passage studied; he need not write the answers if he be taught that the mind can know nothing but what it can produce in the form of an answer to a question put by the mind to itself” (128).

Number 7: “What does it remind me of?” (Laws). Thus we begin building connections among books and subjects. One of Charlotte’s principles is that “education is the science of relations.” As we build relationships with various branches of study, we are actually building our relationship with the Master Mind of all knowledge.

Practically speaking, what do these musings mean as we gather our readers around the table with their books?

First, understand the teacher’s role. Charlotte says, “Thus it becomes a large part of the teacher’s work to help children deal with their books” (163). What a relief to have such a clear focus! We are helping our children grow into adult readers.

Second, teach them a few good reading practices. When adult readers pick up a book, they scan the back matter, the table of contents, and the author’s bio. They flip back through the previous chapter before starting the next one. How simple to teach our growing readers to do the same.

Charlotte also advises:

“Let marginal notes be freely made, as neatly and beautifully as may be, for books should be handled with reverence. Let numbers, letters, underlining be used to help the eye and to save the needless fag of writing abstracts” (128).

We should have our students read with pencils in hand. They can lightly underline important characters, places, definitions, and main ideas. They can draw arrows to highlight especially important ideas, number a sequence of events or arguments, and draw question marks beside puzzling passages.

Third, don’t overdo it. We could easily go overboard in our zeal to try these other ways. But a few practices, a thoughtful question here and there, and a little underlining go a long way. Charlotte warns, “These few hints by no means cover the disciplinary uses of a good school-book, but let us be careful that our…mechanical devices to secure and tabulate the substance of knowledge do not come between the children and that which is the soul of the book, the living thought it contains” (128).

May we and our children grow together as observant, thoughtful, and adventurous readers.

Sources

Adler, Mortimer J. How to Read a Book. Simon & Schuster, 1972.

De-Celles-Zwerneman, Jeannette. Teaching Fiction from the Inside Out. Cana Academy, 2016.

Laws, John Muir. The Nature Journal Connection. “Episode 2: I Notice, I Wonder, It Reminds Me of…” johnmuirlaws.com

Lewis, C.S. An Experiment in Criticism. Cambridge, 2013.

Loughran, Mary Francis. Leading a Discussion on a Work of Art. Cana Academy, 2018.

Mason, Charlotte. School Education. Wilder, 2008.

Leave a comment